Brokerdealer.com blog update courtesy of extracts from 29 Dec edition of the Wall Street Journal, with reporting by Evelyn M. Rusli

Brokerdealer.com blog update courtesy of extracts from 29 Dec edition of the Wall Street Journal, with reporting by Evelyn M. Rusli

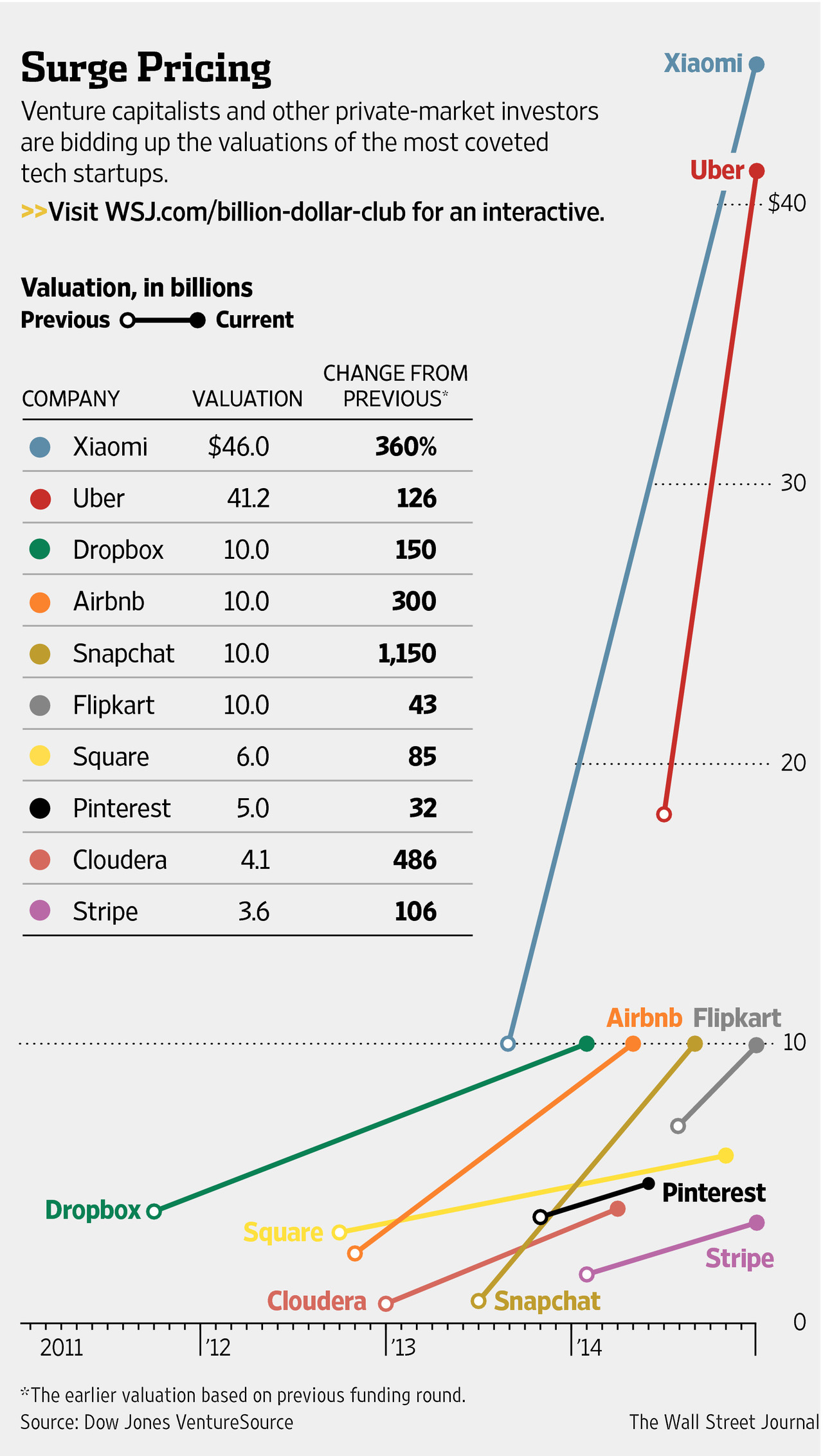

As brokerdealers, investment bankers, institutional investors and entrepreneurs “close the books” on 2014, all will agree this has been a remarkable year in which “billion dollar valuations” have seemingly been the norm. Most notably, technological start-ups have enjoyed increasing valuations with each subsequent round of financing from private equity and venture capital firms, albeit many financial industry professionals are wondering whether those valuations can carry over when these private companies embark on initial public offerings (IPOs).

While “Wall Street” protagonist Gordon Gekko coined the phrase “Greed is Good!,” the Broker-Dealers mantra for 2014 was “Funding is Fun!”

Below please find highlights of the WSJ article.

Chinese smartphone maker Xiaomi Corp. is now officially the world’s most valuable tech startup, worth $46 billion—the exclamation point on a year of extraordinary valuations.

Valuations placed on tech startups world-wide stretched to record heights in 2014 and accelerated at an exceptional pace, even when compared with the late 1990s dot-com boom.

Xiaomi is just the latest example. On Monday it raised more than $1 billion from investors, giving it the $46 billion overall valuation. Only Facebook Inc. raised capital at a higher value from private investors, at $50 billion in 2011.

This year, venture capitalists, mutual funds and big banks bestowed valuations of $1 billion or more on about 40 startups world-wide, doubling the number of such companies at the start of the year, according to research firm Dow Jones VentureSource.

Adjusted for inflation, the current roster of 70 “billion dollar” startups globally is nearly twice as large as the number during the boom years 1999 and 2000.

A “startup,” in this case, is loosely defined as a young, private company backed by venture capital, with overall valuations derived from the price that pre-IPO investors pay for a fraction of the equity.

Surveying the unprecedented valuations in the private market, “I have trouble drawing a parallel,” said Ted Schlein, a general partner at venture-capital firm Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, adding that his firm is trying to exercise “aggressive restraint” as it looks for new investments.

Perhaps more astonishing than the dollar figures was how fast they were achieved. In November, investors paid $1.2 billion for a stake in Uber Technologies Inc. that valued the five-year-old car-hailing service at $41.2 billion, almost 12 times the price set by venture capitalists last year. The valuation of Pure Storage Inc., a vendor of data-storage equipment, tripled to $3 billion in April after less than a year. Slack Technologies Inc. was valued at $1.1 billion in October only a year after releasing its popular work-collaboration product.

In short, 2014 was the year the tech sector went into hyper-drive.

Before this year, only Facebook and Chinese online retailer JD.com Inc. commanded a valuation higher than $10 billion among private companies backed by venture capitalists, according to VentureSource. This year, six startups raised capital at that level or higher.

The prevailing theory behind the investment rush: Technology is overtaking nearly every major industry, from city transportation and hospitality to education and health care. And real businesses are being built, bullish backers say, not the revenue-less startups from those heady dot-com days in the late 1990s, when excitement over the Internet led to a tech-stock bubble that burst in early 2000.

Many of the companies in today’s billion-dollar club, such as Uber, Xiaomi, home-rental site Airbnb Inc., Web storage company Dropbox Inc. and data-mining startup Palantir Inc. are said to be generating tens if not hundreds of millions of dollars annually.

Airbnb, which is seeking to upend the hotel industry, was tagged with a $10 billion valuation in April, about 40 times its revenue of roughly $250 million in 2013. That revenue had doubled from the previous year, people familiar with the matter previously told The Wall Street Journal. Dropbox, also with a $10 billion valuation, had expected sales of more than $200 million in 2013, up from $116 million the year earlier.

Other companies, like messaging service Snapchat Inc. and online scrapbooking site Pinterest Inc., have barely started making money. Investors are betting those companies can capture audiences that will eventually translate into big money, à la Facebook.

Billionaire venture capitalist Peter Thiel , an early investor in Facebook, says on balance the field of startups doesn’t feel overvalued. The sum of billion-dollar-plus valuations in the U.S.—at roughly $160 billion—would still be less than half of Google Inc. ’s $365 billion market cap, he says.

Others are less sanguine.

“Without question in some sectors there is a pricing balloon bubble in late stage,” said Peter Fenton, a partner at Benchmark, an early investor in Uber, Dropbox and Snapchat. “At some point, these companies will be held accountable for their financials.”

The pricing party is being partly driven by the endowments, foundations and pension funds that back venture firms like Benchmark. Low interest rates and the prospect of juicy returns—inspired by success stories like Facebook, Google and Apple Inc. —are encouraging these firms to pour money into venture capital.

Venture firms have raised more than $32 billion this year, up 60% from last year’s total, though still well below the $121 billion (inflation adjusted) raised in 2000, according to VentureSource.

The latest figure, however, doesn’t include the dry powder from mutual funds such as BlackRock, T. Rowe Price and Wellington Management, or from hedge funds and big banks, all of which are bidding up prices.

Andrea Auerbach, a managing director at Cambridge Associates who meets with about 700 venture firms a year and advises foundations and other big institutional investors, says venture capitalists increasingly call her to pitch “pre-IPO funds.” The buzz-phrase conjures memories of the dot-com boom, when investors rushed into tech startups ahead of their initial public offerings. It is a sign, according to Ms. Auerbach, that investors are plowing money into startups based on momentum instead of fundamentals.

“There are managers trying to pursue this tactic—and it’s a tactic, not a strategy—of investing in pre-IPO companies,” said Ms. Auerbach. “There’s a clock on this and they’re running out of time.”

At least 30 companies have gone public in the U.S. with lower prices than they were worth in private stock sales or option grants in the prior 90 days, according to Valuation Advisors, which conducts valuations for private companies. Mr. Fenton of Benchmark sits on the board of business software company Hortonworks Inc., whose bankers cut its $1.1 billion valuation in half in December ahead of its IPO to entice investors. The maneuver worked to a degree—its stock rose 65% in the IPO. But the company, which lost $86.7 million on revenue of $33.4 million for the first nine months of the year, is trading slightly below a $1.1 billion market value.

Some warn that the winds will eventually shift in Silicon Valley and the easy money will end, possibly leading to a trail of destruction akin to the dot-com crash, including company failures and investor losses.

Mr. Fenton, whose firm Benchmark has been closely tracking companies’ spending rates this year, sees reckless behavior as the real devil underneath the big valuation numbers.

“Are we creating a generation of companies whose behavior has been poisoned by easy capital?” Mr. Fenton said.

For the entire story from WSJ, please click here.