Brokerdealer.com blog update courtesy of William Watts from MarketWatch.

Brokerdealer.com blog update courtesy of William Watts from MarketWatch.

Brokerdealers around the world were shocked after the Swiss National Bank unexpectedly announced on Thursday that they would be scrapping a three-year-old cap on the franc. As a result, it sent the currency soaring against the euro while stocks plunged out of fear. Although the market has seemed to bounce back caution should still be taken.

Don’t be too quick to look past the turmoil that swept global financial markets after Switzerland’s central bank unexpectedly scrapped a cap on the value of its currency versus the euro.

While European and U.S. equities largely regained their footing after a panicky round of selling in the wake of the decision, dangers may still lurk in some corners of the market. Here are the potential shock waves to look out for:

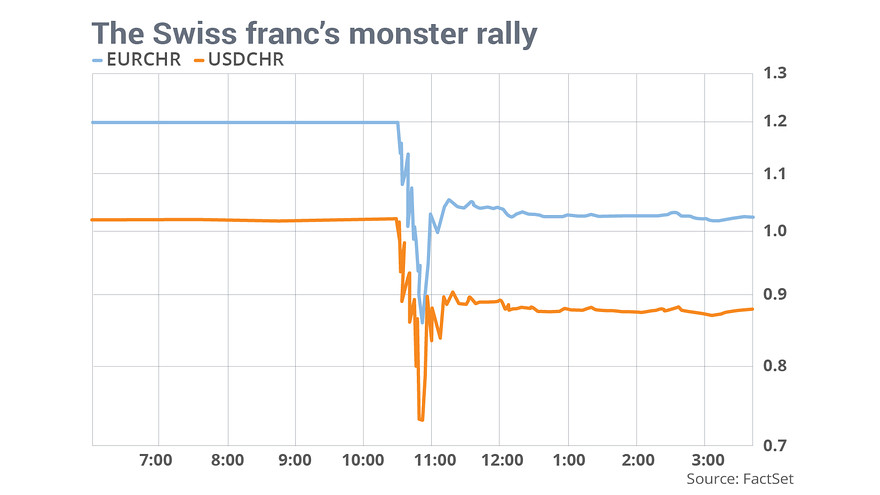

Needless to say, the Swiss franc, which had long been held down by the Swiss National Bank’s controversial cap, exploded to the upside. The euro EURCHF, +0.66% is down 15% and the U.S. dollar USDCHF, +1.69% remains down nearly 14% versus the so-called Swissie after having plunged even further in the immediate aftermath of the move.

Since the Swiss National Bank had given no indication it was set to move — indeed, it had previously said it would defend the euro/Swiss franc currency floor with the “utmost determination” — investors were holding large dollar/Swiss franc and euro/Swiss franc long positions, noted George Saravelos, currency strategist at Deutsche Bank, in a note.

As a result, the moves Thursday likely resulted in some big losses on investor portfolios holding those positions, he said.

“This effectively serves as a large VaR [value-at-risk] shock to the market, at a time when investors were already sensitive to poor [profit-and-loss] performance for the year,” Saravelos wrote.

The Wall Street Journal reported that Goldman Sachs on Thursday closed what had previously been one of its top trade recommendations for 2015: shorting the Swiss franc versus the Swedish krona SEKCHF, +1.26% after the franc jumped as much as 14% on the day versus its Swedish counterpart..

Douglas Borthwick, managing director at Chapdelaine Foreign Exchange, said forex participants are bracing for aftershocks.

“We expect that few risk-management algorithms in G-20 currencies were prepared for greater than 20% moves in a currency pair, for this reason the chance of a binary outcome is significant,” he said, in a note. “Either participants gained or lost considerable amounts.”

Volatility

The Swiss National Bank’s move serves to underline the theme that volatility is back and here to stay.

For U.S. companies, trade exposure to Switzerland is small. And that means the direct impact is likely to be more of a ripple than a wave, said Wouter Sturkenboom, senior investment strategist at Russell Investments in London.

But the turmoil that followed the decision shows that markets are vulnerable to shifts by central banks which have largely been on hold since implementing a range of extraordinary measures in the aftermath of the financial crisis, he said.

“It is adding to this general disquiet in markets that things are volatile and things are changing and central banks are changing,” Sturkenboom said in a phone interview.

“I think that’s maybe the underlying cause [for the volatility in U.S. stocks], especially when you’ve had such a good run; valuations in the U.S. are stretched and expensive,” he said.

Emerging markets

Investors will also likely keep an eye on European banks exposed to central and Eastern Europe. Before 2008, households in several countries in the region, particularly Hungary and Poland, took out mortgages denominated in Swiss francs, attracted by low rates, noted William Jackson, senior emerging markets economist at Capital Economics.

Those households got a shock in 2008-09 and in 2011 when the franc rose, boosting debt servicing costs. Another 15% jump in the franc against most Central and Eastern European currencies Thursday morning could lead to further worries, Jackson said, though he argued that the situation appears much more manageable than in the past.

In Hungary, a law allows households to convert foreign-currency mortgages into forint-denominated mortgages at the exchange rate that prevailed in 2014, Jackson notes, while in Poland, the Swiss franc lending was restricted to higher quality borrowers.